The Piccolo Soloists

The piccolo first made its

presence felt in the eighteenth century but it wasn’t until the following

century that its use became more widespread in orchestras. The instrument

evolved from fife to Boehm system much as the concert flute and more and more

composers included a piccolo part in their orchestral scores throughout the

nineteenth century. However, it soon became apparent that piccolos demanded

special requirements from the players.

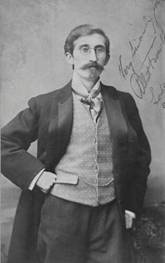

Macaulay Fitzgibbon

maintained that the great piccolo players such as Robert Frisch, Harrington

Young, Charles le Thičre and George Roe

etc. did not shine very pre-eminently as flute players. There may well be some

truth in his thought on the matter. The tighter embouchure required for piccolo

playing may well adversely affect flute tone for some players. Switching

between metal flute and wooden piccolo can cause a player

difficulties. Wooden piccolos rarely have a lip plate and the tighter

embouchure needed for the small hole is much more tiring for the player to

maintain over a long period of time. The smaller instrument requires more air

speed and breath pressure than the flute. Lip position, air pressure and the

small size of the instrument are all critical factors affecting intonation.

Nevertheless, the piccolo

really came into its own with the advent of recording equipment such as

Many virtuoso performers were

recorded from the 1890’s and on into the twentieth century simply because the

piccolo was one of the most suitable instruments to record. Its loud, clear and

high pitched voice was admirably suited to the technical process. The early

recording companies required short pieces from composers because of the

limitations imposed by the current technology and the performers were happy to

thrill their growing audience through their own prowess and the opportunity of

technical display offered by these short pieces. As recordings were made and

sold throughout

In

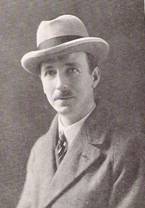

Eli Hudson

Albert Fransella

A couple of years after

Like Fransella, James Wilcocke was a well respected member of the

James Wilcocke Jean Gennin

After about 1910 virtuoso

piccolo recordings began to give way to a repertoire of

music for small ensembles playing classical works although the Gennin brothers and Gordon Walker (1885-1965)

continued to record piccolo pieces well into the late 1920’s.

Belgian born Jean Gennin (b.1886) and his brother, Pierre, played with

Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra from about 1913. Under the direction of Dan

Godfrey they recorded piccolo and flute

duets composed by Jean. His Fluttering

Birds for two piccolos and orchestra was recorded on

Gordon Walker

In London Gordon Walker had

already made a number of piccolo solo recordings for Zonophone

It has been estimated that

between 1889 and 1930 well over a thousand piccolo solos were composed and

performed in outdoor bandstands across the

John S. Cox

John S. Cox

The Irishman John S. Cox

(1834-1902) was known to be a good piccolo player who also composed a

number of solos for the instrument. He first played in Gilmore’s band before

being appointed by Sousa in 1892. From 1900 Marshall Lufsky

(1878-1948) and Darius Lyons (1870-1926) played together and toured

with Sousa. Between 1902 and 1909, Lufsky made nearly

100 recordings as piccolo soloist, and from 1906 became flautist in the studio

orchestra of the Columbia Phonograph Company, a position he held for fourteen

years.

During the 1920’s he

occasionally played at the Metropolitan Opera House and with the New York

Philharmonic. His recording of Nightingale

Polka made with Prince’s band for

Lufsky’s partner, Darius Lyons, played with the Victor Herbert

Orchestra and the Savage Opera Company in

Henry Heidelberg (b.1872) filled the vacancy in Sousa’s band left by

Recording companies in

Piccolo players and composers of popular

pieces for the instrument were numerous in the early years of the twentieth

century but, in more recent times, players have had to prove themselves in the

orchestral world, for it is here that the instrument has found its niche. In a

sense, today’s orchestral players are soloists every time they raise the

instrument to their lips, as the sound of the piccolo is one of the most easily

detected by ear of all the sounds an orchestra can offer.

© Stuart Scott, 2011