HALLÉ FLUTES

Flautists of the Hallé Orchestra

In 1774 no fewer than 26 flautists established the

Gentlemen’s Concerts in

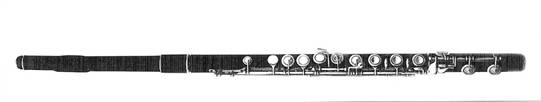

The orchestra was formed in the mid- nineteenth century

during a period of great invention for the flute when almost all aspects of the

instrument were being modified, changed or improved. Of the numerous models

available at this time, professional flautists eventually took up the Boehm

flute unanimously and by the end of the century most British orchestral players

were using Rudall Carte Boehm system

cocuswood flutes.

By the mid 20th century, Hallé flautists were

still using wooden instruments. They produced a tonal blend of dense, firmly

centred sound characteristic of most British orchestras at that time and some

players supported the wooden flute nearly to the end of the 20th

century. Hallé principal, Roger Rostron retained a wooden instrument until the

1980’s.

It is not my intention to open a

debate on wood versus metal but merely to point out the kind of instrument used

by many of the flautists to be mentioned here.

Training and experience in the late 19th and early 20th

century differed greatly from that of more recent times. Then, many of the

Hallé’s flautists had gained their experience in a variety of ensembles.

Visiting opera companies flourished in the 1890’s and regularly gave

performances in

Some of them had little formal training as we know it today

but found that the advice of their teachers plus their varied early experiences

served them adequately. They quickly became good sight readers. They were

flexible players and proud of their achievements. Principals often showed their

prowess in solo pieces accompanied by the rest of the orchestra and in their

turn became teachers of the next generation.

Players of the early Hallé years took on teaching

appointments at the Royal Manchester College of Music or taught privately. And

so started a long line of teacher-pupil

relationships in Hallé flautists spanning more than 100 years and

establishing a tradition which is unique in British orchestras.

So who were these players?

So who were these players?

Hallé’s first principal flute was one, Edward De Jong (1837-1920). From the very

beginning (1858), he maintained a high profile with regular solo appearances

and Boehm’s Fantasias figured highly in his repertoire. Between November 1858

and January 1865 (seven years) De Jong played no fewer than thirteen solos at

Hallé concerts, including his own ‘Scotch Airs’ and Fantasias.

Following the performance of his own rather difficult

‘Fantasia on Faust’ in 1867, there were fewer opportunities for solo work. Hallé

concerts saw an increase in vocal rather than instrumental soloists and this no

doubt influenced De Jong’s decision to leave the orchestra and set up his own

Saturday Popular Concerts.

Charles Hallé considered this a rival venture of course, but

De Jong had an orchestra of 60 players, including John Taylor, principal flute

and Eugene Damaré (1840-1919), who appeared regularly as piccolo soloist.

Although Damaré eventually wrote more than 400 pieces, he is now only

remembered perhaps for his little solo entitled, “The Wren”.

De Jong’s concerts pleased audiences and critics but

financial constraints soon brought them to an end. However, he continued to

play as soloist and conduct concerts at venues such as Buxton,

Edward De Jong had started life in

Of his playing, another writer was to note that – “in his

hands the flute became articulate…….it literally sings, especially on the lower

register”. This can still be ascertained today, to some extent, when listening

to his 1904 recording of “Auld Robin Gray”, where his ringing tone, firmly

centred, shines through the surface noise of the cylinder. He was about 67 when

he made this recording –

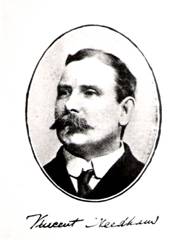

Following De Jong as Hallé principal, Jean Firmin Brossa (1839-1915) was 32 years of age

when he arrived in

Following De Jong as Hallé principal, Jean Firmin Brossa (1839-1915) was 32 years of age

when he arrived in

However, his Hallé tenure began in the De Jong tradition of

presenting himself as soloist. Following

his

Nevertheless, during Brossa’s 29 years as Hallé principal,

opportunities for further work as a soloist were few and far between but his

performance of Bach’s Suite No.2 in B minor in 1899 – a first for

The programmes of the 1880’s were varied and Charles Hallé,

then in his sixties, continued to seek out new works for his orchestra. His

friendship with Berlioz resulted in Brossa taking part in the first complete

performance in

The Boehm flute at this time was still undergoing minor

changes in design: changes mainly concerned with the key system in attempts to

offer flautists greater facility in fingering. Brossa developed an extra F#

device. He worked on and perfected a small touch key for use by the third

finger of the right hand. It is still found on many flutes in use today.

This little touch key duplicates the F# action of the regular

key and it has advantages in moving between E and F#. It makes it easier to

trill and improves the F# through better venting. The year 1895 seems to be the

earliest recorded sale of a flute with Brossa’s F# key fitted, the work being

carried out by Rudall Carte who offered it as an optional extra.

That same year marked the death of Charles Hallé and his

orchestra was left in a state of flux. By 1900 Brossa had retired from

orchestral playing but continued to perform as soloist at concerts outside

His contribution had been lengthy, showing great loyalty to

the orchestra, dedication to pupils and the furtherance of the flute as a solo and

orchestral instrument.

It was during Brossa’s time as

principal that another interesting character turned up. In 1876 the Hallé flute

section was increased in number to three. Brossa and Henry Piddock were joined

by Fred Lax (b.1858) – piccolo player

extraordinaire. He was 18 at this time but his name was already appearing to

the forefront of British flautists.

It was during Brossa’s time as

principal that another interesting character turned up. In 1876 the Hallé flute

section was increased in number to three. Brossa and Henry Piddock were joined

by Fred Lax (b.1858) – piccolo player

extraordinaire. He was 18 at this time but his name was already appearing to

the forefront of British flautists.

He was a soloist at heart and only stayed in Manchester for

one season before touring extensively, eventually ending up in America,

settling in Baltimore round about 1920. His business card described him not

only as a composer and arranger but teacher of flute, clarinet, flageolet,

saxophone and harmony, as well as being an agent for Bettoney Woodwind

Instruments.

He was also an early recording artist with the Stanzione

& Finkelstein Company, for whom he recorded a performance of ‘Lo, here the

gentle lark’ in 1908 - an arrangement

by the clarinettist, Charles le Thiere.

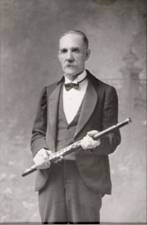

From 1900, Vincent Needham

continued the now established line of Hallé principals, having studied with

both De Jong and Brossa.

Within the next three years his reputation was such that he

was in demand as an orchestral and solo flautist throughout the north of

Richter took him to the Birmingham

Festival in 1903, along with his distinguished colleagues, E.S.Redfern (who was

later to be principal himself), Thomas Marsden,

Fred Hatton (the brilliant piccolo player who never thought twice about

Tchaikowsky’s 4th) and William Dixon ( well

known tea drinker!). This very strong flute section was engaged continuously

for the Festival and it was at one of these concerts that Richter first

complimented

Richter took him to the Birmingham

Festival in 1903, along with his distinguished colleagues, E.S.Redfern (who was

later to be principal himself), Thomas Marsden,

Fred Hatton (the brilliant piccolo player who never thought twice about

Tchaikowsky’s 4th) and William Dixon ( well

known tea drinker!). This very strong flute section was engaged continuously

for the Festival and it was at one of these concerts that Richter first

complimented

It was, however,

He had done much to help Richter popularise Bach’s music in

On

There seems no doubt that

Following his untimely death, friend

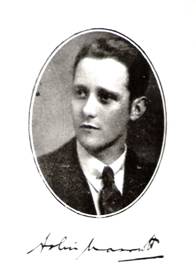

and colleague Edward Stanley Redfern took

over as principal. Known as Teddy to all his friends, he had played second

since 1900 but even at that time he was a player of wide experience and

distinction.

Following his untimely death, friend

and colleague Edward Stanley Redfern took

over as principal. Known as Teddy to all his friends, he had played second

since 1900 but even at that time he was a player of wide experience and

distinction.

At the tender age of 15 he had given his first solo concert

at St. George’s Hall in his home town of

On this and other such instruments he played under Riviere at

But the position in which he took great pride was that of

principal flute for the Grand Opera at

When Redfern took over as Hallé principal in 1916 the

orchestra was almost entirely under the direction of Sir Thomas Beecham.

Programmes included much recent and contemporary music – works by Delius,

Strauss and Debussy. The opportunity for solo work with the Hallé didn’t

present itself but no doubt there were many in his audiences who remembered his

performances of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No.4 with Vincent Needham in

previous days.

By 1920 Redfern’s professional life was seriously interrupted

by ill health and he died the following year. It was an early end to the life

of a remarkable flautist. His most genial and kindly disposition, his rich,

smooth tone and remarkable technique were noted by writers in the 1920’s. His

obituary in the Manchester Guardian stated that, “Mr Redfern had a refinement

of style that was quite his own and something apart from mere dexterity on the

instrument”.

Two other members of the flute

section during Redfern’s tenure as principal were William

Thorn (1878-1937) and Joseph Lingard

(1880-1969). Bill Thorn had joined in 1916 when Redfern became principal

and was a pupil of Thomas Marsden. He

gave nearly 20 years service to the orchestra and both he and Lingard became

the first Hallé flautists to broadcast for the BBC from

Two other members of the flute

section during Redfern’s tenure as principal were William

Thorn (1878-1937) and Joseph Lingard

(1880-1969). Bill Thorn had joined in 1916 when Redfern became principal

and was a pupil of Thomas Marsden. He

gave nearly 20 years service to the orchestra and both he and Lingard became

the first Hallé flautists to broadcast for the BBC from

When the Hallé season opened in 1921, Joe Lingard occupied

the principal’s chair. He had already had a taste of life as an orchestral

principal having had to stand in for Redfern during those final days of ill

health. He was well aware of what was expected of him having served with two

great principals and continued the tradition in fine style introducing Mozart’s

Concerto for Flute & Harp to

His music making outside the confines of the Hallé concerts

saw a new departure for it was in 1924 that the BBC started making regular

broadcasts. Joe made over 36 live broadcasts between 1924 and 1934, many of

which were solo recitals accompanied by Eric Fogg at the piano. A broadcast of Harty’s “In Ireland” with the

composer at the piano on St. Patrick’s Day in 1929 must have been a special

occasion for both performers. Sadly, these live broadcasts don’t seem to have

been recorded so it is fortunate that Harty’s attention at that time was

directed towards recording with the Hallé.

In 1929 a 78 rpm recording of Rimsky Korsakov’s “Flight of

the Bumble Bee” appeared, thus giving us a chance to hear for ourselves the

precision fingering and total control exhibited by Lingard. Even through the

surface noise of the disc his performance can be followed note for note. His

tone is large and his technique flawless. It is difficult to decide where he

breathed!

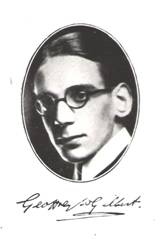

Joe Lingard died in 1969 after having spent more than 40

years as a professional. A good number of those years were spent teaching at

the Royal Manchester College of Music and he was responsible for the training

of many excellent flautists – not least of all, Geoffrey

Gilbert, who spent 3 years as a Hallé flautist playing alongside his

teacher, eventually taking over as principal himself  for the 1934-35 season.

for the 1934-35 season.

In 1933 Harty had resigned his Hallé conductorship and the

years immediately following were difficult years for the orchestra. Sir Thomas

Beecham was trying to co-ordinate things but soon offered Gilbert a position in

his London Philharmonic Orchestra. And so, at 19, Gilbert was a principal of

that great body of musicians.

The rest of his career is well documented but let it not be

forgotten that in addition to holding appointments with major orchestras under

great conductors, Gilbert premiered in

He was a prominent teacher too, who helped considerably with

the adoption of the so-called French style by English flautists and when he

died in 1989, aged 74, The Times described him as “the most influential British

flautist of the 20th century”.

Replacing Gilbert as Hallé principal

in 1935 was Vernon Harris, a pupil of Vincent

Needham. In time honoured fashion he appeared in Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos

and Debussy’s L’apres midi was performed so often during the late 1930’s and

early 40’s that of all Hallé principals, Vernon Harris must hold the record for

delivering that opening solo, in which he was able to demonstrate the

characteristic limpid sound quality and controlled vibrato only he could

produce in such pieces.

Replacing Gilbert as Hallé principal

in 1935 was Vernon Harris, a pupil of Vincent

Needham. In time honoured fashion he appeared in Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos

and Debussy’s L’apres midi was performed so often during the late 1930’s and

early 40’s that of all Hallé principals, Vernon Harris must hold the record for

delivering that opening solo, in which he was able to demonstrate the

characteristic limpid sound quality and controlled vibrato only he could

produce in such pieces.

In September 1941, Sargent directed a Hallé concert at the

Pier Pavilion, Llandudno which featured Vaughan Williams’s Greensleeves

Fantasia. The opening solo beautifully delivered by Vernon Harris can be heard

in a recording made for HMV shortly after the concert.

Made about the same time, a recording of Delius’s “Intermezzo

from Hassan”, conducted by Constant Lambert shows him as a fine player with a

lovely sound.

Vernon Harris left the orchestra for the BBC Northern in 1943

and the next 3 years saw the principal’s  chair occupied by Arliss Marriott. Bill Marriott, a pupil of the

famous Robert Murchie, was well known in

chair occupied by Arliss Marriott. Bill Marriott, a pupil of the

famous Robert Murchie, was well known in

A young Oliver Bannister

(b.1926) was appointed at the same time and in their first season together they

gave several very successful performances of Bach’s 4th Brandenburg

Concerto.

By 1945, Marriott had left for

Following the tradition of previous principals, Oliver

Bannister - pupil of Joe Lingard and staunch supporter of the wooden flute –

was heard as soloist on a number of occasions. There were performances of

Ibert’s “Flute Concerto”, Frank Martin’s “Ballade”, the Cimarosa “Concerto for

Two Flutes” with Bill Barlow and no fewer than five performances of the Bach

Suite in B minor, two of which were conducted by Hindemith.

Of

such performances the critics noted

Oliver Bannister’s dazzling skill and brilliant technique. Hallé leader,

Martin Milner was later to write that his musicianship was “of such good

quality that the other woodwind all played to him – intonation, phrasing,

everything”.

Of

such performances the critics noted

Oliver Bannister’s dazzling skill and brilliant technique. Hallé leader,

Martin Milner was later to write that his musicianship was “of such good

quality that the other woodwind all played to him – intonation, phrasing,

everything”.

He left the orchestra in 1963 to take up the position of

principal flute at

Listen to him here in this recording of “The Aviary” from

Saint Saens’s Carnival of the Animals made in 1954, where everything is

beautifully controlled.

The artistry of the Hallé wind players during Oliver

Bannister’s tenure as principal flute was recognised by everyone as being of

the highest quality and for their successors, it was indeed a hard act to

follow.

The next five years or so brought many changes and for the

first time in Hallé history the orchestra supported an all metal flute section.

However, the orchestra was fortunate in finding players of high calibre to

carry it through a difficult period. Players such as Douglas Townshend, Peter Lloyd, Chris

Taylor, Fritz Spiegl and Frank Nolan.

The arrival of Roger Rostron (b.1937) as principal in 1967

brought not only the return of the wooden flute to the Hallé but a long period

of much stability.

The arrival of Roger Rostron (b.1937) as principal in 1967

brought not only the return of the wooden flute to the Hallé but a long period

of much stability.

Precision, assurance and musicality always marked Roger’s

playing and a brilliant, but never harsh, tone

in the higher register and a beautiful mellowness in the

lower, is there for all to hear in the recordings made with the orchestra.

There were, of course, the traditional solo appearances with

the orchestra – spanning the years 1969 to 1991 – including Bach Brandenburg

Concertos. Other works, such as the Mozart Flute & Harp Concerto and

Devienne’s Flute Concerto No.8 remain in the memory too.

One highlight of the 1968-69 Hallé season was a performance

of “The Childhood of Christ” and I well remember the famous trio for two flutes

and harp admirably performed on that occasion under the baton of Andrew Davis.

The 1980’s brought a new departure for Roger Rostron On

With Roger Rostron’s retirement came

what seemed like an endless period of decision as to who would fill the vacant

chair. Various players thought about trying it out for size, including Andrew

Nicholson who remained only for a very short time.

With Roger Rostron’s retirement came

what seemed like an endless period of decision as to who would fill the vacant

chair. Various players thought about trying it out for size, including Andrew

Nicholson who remained only for a very short time.

However, the orchestra now has a very able principal flute

once again. Katherine Baker, appointed in

2004, is the first woman to fill the position in the whole of the Hallé’s long

history. She continues a fine tradition.

Through the restriction of space, I have confined my comment

to principals, but let it not be forgotten that

a principal alone cannot make a good flute section in any

orchestra. The Hallé has attracted many excellent second flute players and

brilliant piccolo players throughout its history – and continues to do so.

Let us conclude the discussion of Hallé flutes with a happy example of fine

ensemble, control and articulation from Oliver Bannister, Bill Barlow and Bill

Morris in their 1950 recording of ‘Farandole’ from Bizet’s L’Arlesienne.

© Stuart Scott, 2008.

Return to Flute History Main Page